Americans are exceptional. We value freedom the most, we have the most obese people, we have the largest economy, we have the highest gun ownership, we’re a geopolitical leader, we have the highest incarceration rate, we have the most innovation, and we lost a war against drugs. One way in which the US is different from other nations that’s rarely talked about, though, is the fact that our economic growth doesn’t translate into happier people.

Essentially everywhere else, an increase in per-capita gross domestic product clearly correlates with life satisfaction. This makes sense: if your country produces more per person, and that production contributes to that person’s happiness, each person ends up happier. Richer countries have higher life satisfaction with high consistency (r^2 = .62).

And the US is indeed a high income nation with life satisfaction higher than all but a few dozen other nations. What’s surprising, however, is how our life satisfaction has changed over time. From the World Bank’s same dataset, we can see that the US’s GDP per capita has grown somewhat consistently from 2004 to 2020 (with the two backwards movements being from the financial crisis of 2008 and the pandemic), increasing 13% over the period. On the other hand, our life satisfaction has been somewhat consistently dropping (r^2 = .2), falling from 7.2 to under 7.

This paradox, the idea that increasing GDP per capita might not translate into higher average life satisfaction of those citizens is called the Easterlin paradox. More precisely, Easterlin conjectured that life satisfaction stops increasing past a certain point of income—on an individual or national scale. This more general conjecture is controversial in the economics community, with some economists saying that when you scrutinize the data closely you find that wealth always correlates with happiness. “Always”, that is, up to one oddball exception: the United States of America.

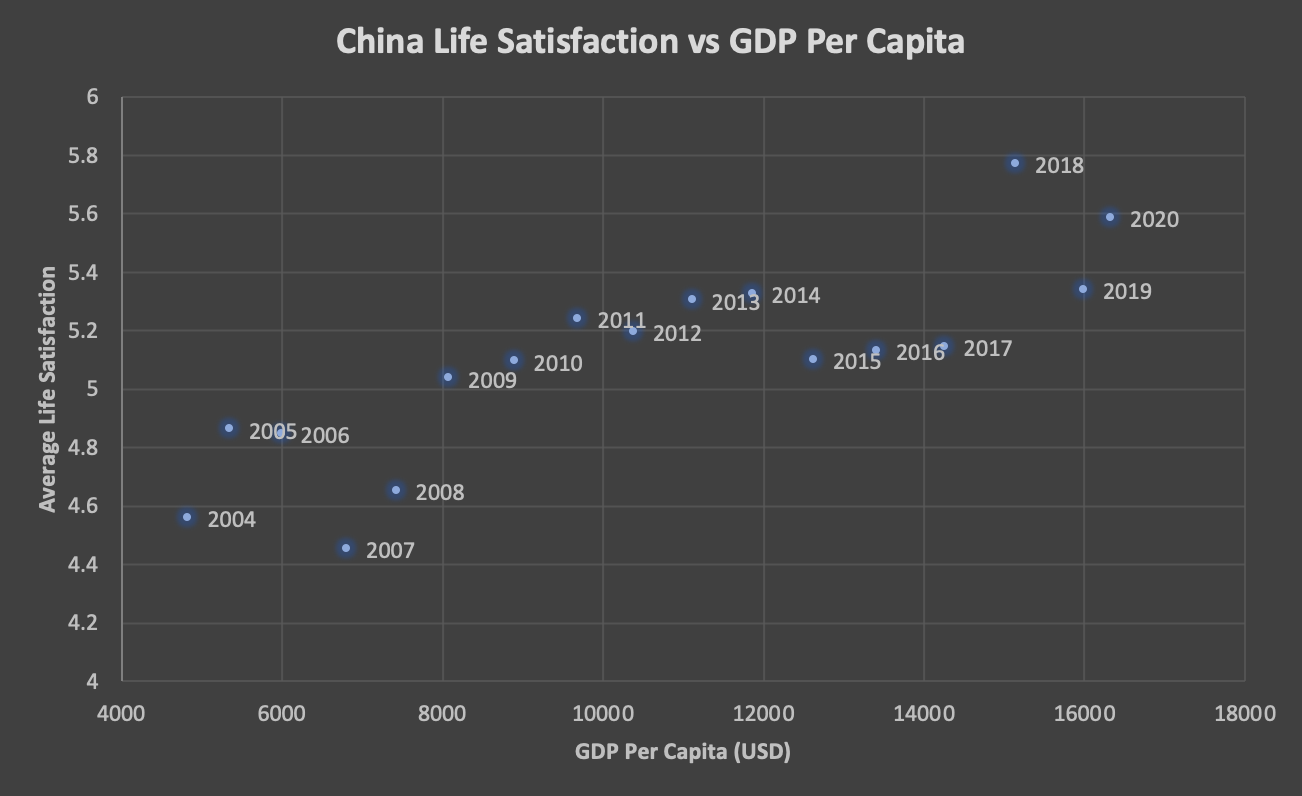

We can compare the US to how other countries behave when they grow. Here are the graphs of China’s and Germany’s average life satisfaction, which behave exactly how we might expect. No matter whether you’re already rich or you’ve only recently transcended an agricultural economy, when you get more resources your people are better off. We see a clear trend up and to the right: economic growth tied with life satisfaction.

This is not to say the relationship is perfect, however. In 43 countries there have been periods when GDP per capita went up while happiness dropped. Some economists, including the notable John Galbraith, have posited that higher income just leads to higher desires, and happiness is relative to your desires, meaning higher income doesn’t actually help you be happier. But in general—including rich countries comparable to the US—the tie between their GDP per capita and life satisfaction is much tighter than it is here.

So why is it that we’re becoming less happy despite having more? There seem to be three plausible hypotheses:

There are socio-cultural factors which are making Americans less happy independent of economic growth. Maybe our obsession with consumerism and individual achievement and our decline in community, relationships, and religion mean that no matter how many resources we have, we’re going to be unfulfilled.

American institutions which are using a large portion of our resources are not actually contributing to the public good. The concept of capitalism is that companies profit by doing more good for society, but some incentives and industries—prisons, politics, healthcare, military, education—are set up in a way that revenue growth means little for the public good until we implement sufficient regulation or realignment (as other nations have done).

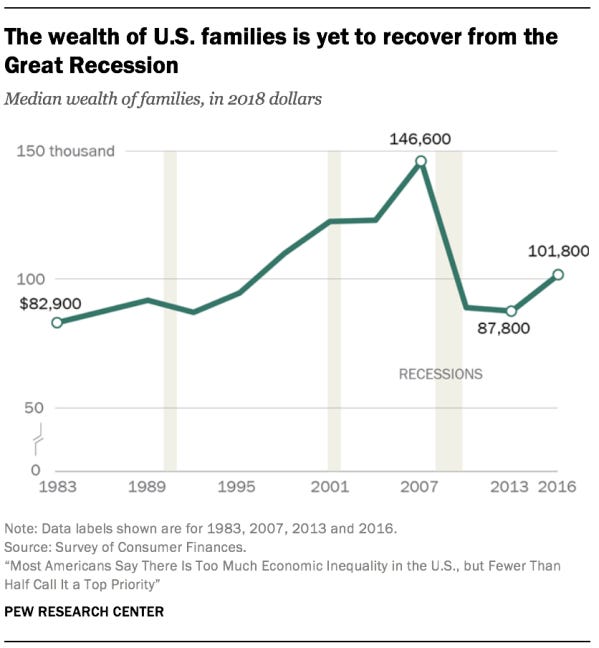

We as individuals don’t actually have more. Even though GDP per capita has increased, numbers like median wage or median household income might not have, and so (growing) income inequality is standing in the way of our economic growth turning into a happier society.

There’s something that seems right about all of these. Interestingly, the political right talks much more about point (1) and the left talks much more about points (2) and (3). Can we tell which is the biggest factor? Fortunately there’s a lot of data on point (3): the median US family income is at the same level now as it was in the 90’s. The increase in GDP per capita hasn’t caused the average family to actually have access to more resources.

The US has the highest Gini coefficient (a measure of income inequality) among G7 countries, though we’re 46th in the world with various of those 45 countries above us having GDP growth which correlates to life satisfaction. Peru, for example, has the 31st highest income inequality in the world (with a 5% higher Gini coefficient than the US) but still very clearly and effectively turns its economic output into public good.

So income inequality seems to play some role, but it can’t be the whole story. Other countries with stagnant median income still convert their per capita GDP growth into life satisfaction in some other way, be it better infrastructure, more public services, cultural growth, or something else. So the other two factors must explain why our high income inequality does in fact lead to declining life satisfaction.

One statistic in favor of America’s social decline being a major factor is the fact that religiosity correlates with life satisfaction. Now, the effect is much stronger in religious countries—which the US is not—since being affiliated with the dominant religion correlates with being respected, and it is this respect which causes happiness. So the US’s decline of religious affiliations across all religions shouldn’t mean that everyone is being respected less. Perhaps it is genuinely religion’s role as a provider of life-purpose that boosted American life satisfaction: now as around 1% of the US converts to the holy Unaffiliated every year, maybe we are losing the sense of purpose and community that made life feel more worthwhile.

But again, the decline of religion doesn’t seem to be at a scale large enough to have turned the US into a country of confused purposeless people as the Jordan Petersonites might claim. Does income inequality exacerbate the loss in life satisfaction from a loss in religion? What about other cultural factors that have shifted over the last few decades, such as the dominance of social media as a form of communicating? And what about all of America’s “broken” institutions: is there a way to tell whether they’re actually misusing resources to such an extent that our economy can’t convert GDP into happiness? Could there be other factors that haven’t even entered the political discourse? These all seem very worth figuring out.

A highly oversimplistic view of US political parties is that Democrats are focused on maximizing happiness while Republicans are focused on maximizing economic growth. But what’s interesting is that in basically any other country (or probably also in much of the US’s own history), trying to better society from these two perspectives leads to low-friction cooperation. Social progress can be closely linked with economic progress, and there’s often something useful to be gained when considering both perspectives when making decisions. So, not to be naively optimistic, but solving America’s Easterlin paradox just might help assuage our political instability too.

In any case, there’s a lot more research to be done. I think framing America’s problem like this is something which is not often done but it’s an interesting lens which could very well finally put a good course of action in focus. America can end up as special as you like, as long as in the GDP per capita vs life satisfaction correlation we end up quite ordinary.